Faith Nyasuguta

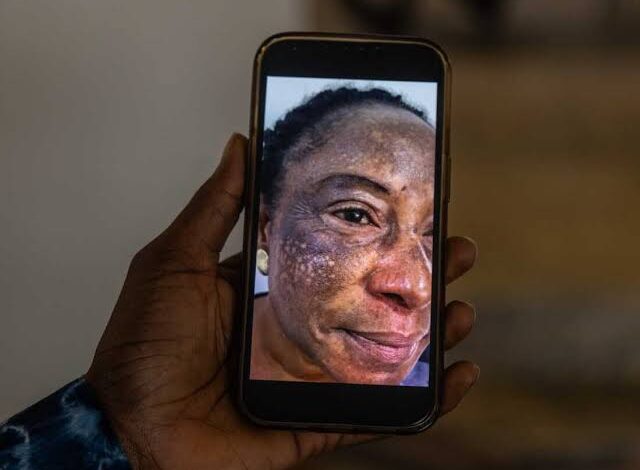

In West Africa, a troubling new trend is coming to light – one that dermatologists warn could become a full-blown health crisis. A 65-year-old woman from Togo recently died after suffering from three cancerous tumours on her neck. Doctors believe the cause was long-term use of skin-lightening creams, which she had applied for over 30 years. Her story is not unique, and researchers say this is part of a much wider, dangerous pattern.

Across Africa, millions of women use creams and lotions to lighten their skin- driven by social pressure, colonial-era beauty ideals, and media portrayals that associate lighter skin with attractiveness and success. But now, these products are being linked not just to rashes and pigmentation issues – but to life-threatening cancers.

Professor Ncoza Dlova, a leading South African dermatologist and head of dermatology at the University of KwaZulu-Natal, warns that removing melanin – the pigment that gives dark skin its colour and natural protection – makes the skin dangerously vulnerable. “Patients with black skin have a natural SPF of about 15,” she explains. “If they remove that melanin with skin-lightening creams, they’re actually removing their natural defence.”

Dlova and other dermatologists are working on a report that details more than 55 cancer cases tied to skin-lightening products. Many of these cases have emerged in Mali, Senegal, and Togo. “If we are getting self-induced skin cancer, that’s a red flag. It’s deeply worrying,” says Dlova. “We need urgent action.”

Skin-lightening products are a multi-billion-dollar industry. Valued at $10.7 billion globally today, the market is expected to soar to over $18 billion by 2033. While once focused mostly on women, these products are now reportedly used on children, and in some cases, even infants.

Many of the creams contain dangerous ingredients like hydroquinone and highly potent corticosteroids, which are illegal in several countries. Hydroquinone has been banned in South Africa since 1990, followed by similar bans in Kenya, Ghana, Rwanda, Tanzania, and Ivory Coast. These bans were introduced after it was discovered that hydroquinone could cause ochronosis – a condition that leads to permanent dark patches and disfigurement.

Even so, enforcement is weak. Despite the bans, these creams continue to be sold on the black market and in unregulated cosmetic shops. “Almost every day, my clinic sees someone suffering from the effects of skin-lightening products,” Dlova says. “Sometimes it’s acne or fungal infections that won’t respond to regular treatments. Other times, it’s permanent stretch marks or worse – skin cancer.”

In Senegal, another study found eight cases of women who had developed cancer after using skin-lightening creams for around 20 years. Two of them died. The products in question contained both hydroquinone and steroids, which when combined, may accelerate damage. “These ingredients can have a synergistic effect – making the harm even greater,” Dlova explains.

Topical steroids are typically used in medicine to treat inflammatory conditions like eczema, but they also lighten skin – making them attractive for cosmetic use. However, long-term misuse can thin the skin, weaken immunity, and lead to severe infections or scarring.

To make matters worse, a warning has been issued by the International League of Dermatological Societies (ILDS). It calls on governments across Africa and beyond to tighten regulation of topical steroid use in cosmetic products. ILDS president Prof Henry Lim says the issue isn’t limited to Africa. Similar reports have come from India and other parts of Asia.

Dlova notes that while hydroquinone bans initially helped reduce complications, problems have surged in the last decade. “It’s gotten worse,” she says. “Now we’re moving from pigmentation issues to actual skin cancer. That’s a major red flag.”

She also links the rise of these products to social media and photo filters, which often promote a fair-skinned beauty standard. “Filters smooth the skin and make it lighter. That constant visual messaging makes people feel that lighter is better,” she says.

Changing this mindset, she argues, will require more than government regulation. Media, marketing agencies, celebrities, and fashion industries all have a role to play. She urges advertisers to feature a diverse range of skin tones and challenges the idea that lighter skin is more beautiful.

“It starts early,” Dlova adds. “We need to introduce skin health education in preschools, teaching children to love and care for their natural skin. And we need to talk about the importance of using sunscreen, not bleaching.”

As awareness of the link between skin-lightening creams and cancer grows, health experts hope the tide will turn. But until then, the demand for lighter skin – and the dangerous products that promise it – shows no sign of fading.

RELATED: