Wayne Lumbasi

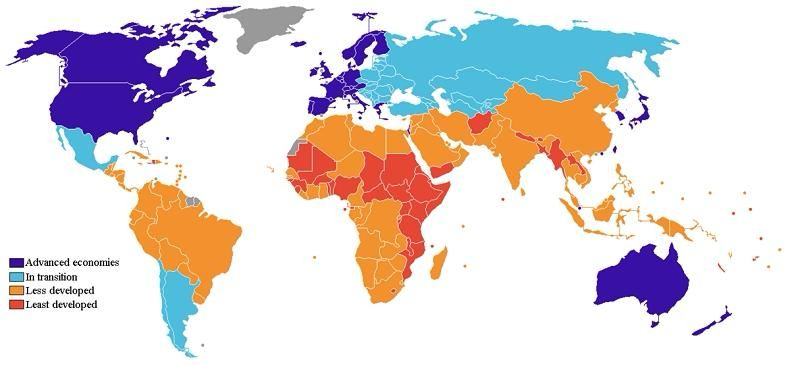

A quarter of developing countries are now poorer than they were before the COVID-19 pandemic, underscoring a deeply uneven global economic recovery, according to the World Bank’s latest assessment of the world economy.

In its newest Global Economic Prospects report, the World Bank finds that while most advanced economies have moved beyond the shock of the pandemic, many developing nations have failed to regain lost ground. By the end of 2025, roughly one in four developing economies still recorded lower income per person than in 2019, meaning living standards for millions of people remain below pre-pandemic levels.

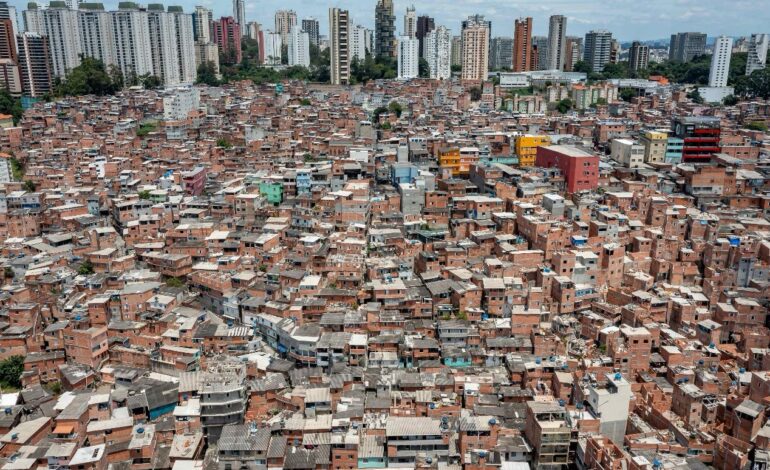

The finding highlights a widening divide between richer and poorer nations. Advanced economies have largely recovered, supported by strong fiscal stimulus, access to cheap financing, and faster productivity growth. In contrast, many developing countries entered the pandemic with weaker financial buffers and have since been hit by a succession of shocks, including high inflation, rising interest rates, currency pressures, and slower global trade.

Population growth has further diluted economic gains in several countries. Even where headline GDP has increased, faster population expansion has meant that income per person has stagnated or declined. Large emerging economies, as well as smaller low-income nations, are among those struggling to translate growth into tangible improvements in living standards.

The World Bank warns that global growth remains too weak to drive a broad-based recovery. Economic expansion is projected to stay modest over the next two years, limiting job creation and slowing progress on poverty reduction. At the same time, high debt levels in many developing countries have reduced governments’ ability to invest in infrastructure, education, and healthcare-areas critical for long-term growth.

Trade fragmentation and policy uncertainty have added to the strain. Slower demand from major economies, alongside rising geopolitical tensions, has weakened export prospects for many developing nations that rely heavily on commodity sales or manufactured goods exports. Private investment has also lagged, reflecting higher borrowing costs and concerns about economic stability.

The consequences are particularly acute in parts of sub-Saharan Africa and other vulnerable regions, where poverty reduction has stalled and fiscal pressures have intensified. The World Bank notes that without faster and more inclusive growth, many countries risk losing a decade or more of development progress.

To reverse the trend, the Bank calls for structural reforms aimed at boosting productivity, improving the investment climate, and strengthening institutions. Expanding access to finance, investing in human capital, and restoring fiscal sustainability are seen as essential steps to help developing economies catch up.

RELATED: