Faith Nyasuguta

An Indian pharmaceutical company, Aveo Pharmaceuticals, is at the center of a growing opioid crisis in West Africa, exporting unlicensed and dangerously addictive drugs that are wreaking havoc in countries like Ghana, Nigeria, and Cote d’Ivoire. A BBC Eye investigation has uncovered how the Mumbai-based company is manufacturing and illegally shipping opioids that are not approved for use anywhere in the world, driving a devastating public health crisis.

The Deadly Cocktail: Tapentadol & Carisoprodol

Aveo Pharmaceuticals produces a range of pills under various brand names, but the core ingredients remain the same, tapentadol, a powerful opioid, and carisoprodol, a muscle relaxant so addictive it has been banned in Europe. The combination of these two substances is highly dangerous, causing breathing difficulties, seizures, and in cases of overdose, death.

Despite the severe health risks, these opioids have become popular as street drugs in West Africa due to their low cost and widespread availability. BBC reporters found packets of these pills, branded with the Aveo logo, openly sold in markets and street corners in Ghana, Nigeria, and Cote d’Ivoire.

Undercover Inside Aveo: Profits Over People

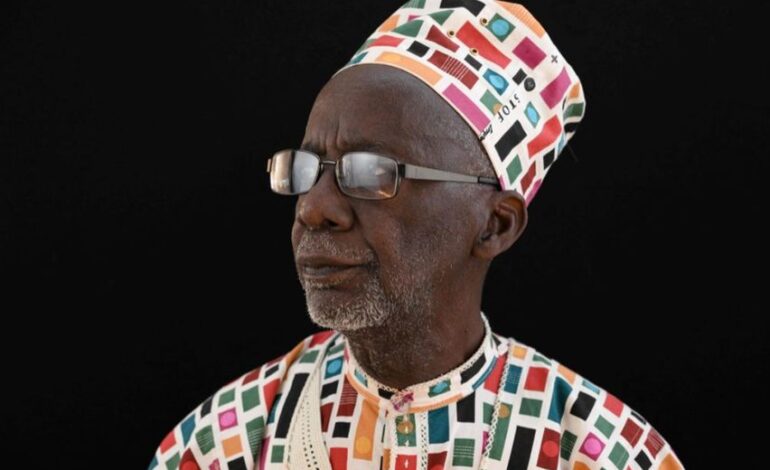

To trace the source of these drugs, a BBC undercover operative, posing as an African businessman, infiltrated Aveo’s factory in Mumbai. Using a hidden camera, the operative filmed Vinod Sharma, one of the company’s directors, openly discussing the sale of these dangerous opioids.

In the secretly recorded footage, the operative told Sharma of his intention to sell the pills to Nigerian teenagers, noting their popularity among young users. Sharma showed no hesitation. “OK,” he replied, even explaining that users could get “high” by taking multiple pills at once. When pressed about the health risks, Sharma admitted, “This is very harmful for the health,” before dismissively adding, “nowadays, this is business.”

This business is not only illegal but deeply destructive. Across West Africa, millions of young people are falling into addiction, with entire communities grappling with the fallout.

West Africa’s Opioid Crisis

In Tamale, a city in northern Ghana, the impact of these drugs is especially visible. So many young people have become addicted that local leader Chief Alhassan Maham has formed a voluntary task force of around 100 residents. Their mission? To raid drug dealers and clear these opioids from the streets.

“The drugs consume the sanity of those who abuse them, like a fire burns when kerosene is poured on it,” Maham told the BBC. One local addict put it even more bluntly: “The drugs have wasted our lives.”

BBC journalists followed the task force on a raid in Tamale’s poorest neighborhoods. They passed a young man slumped on the roadside, barely conscious,locals said he had overdosed on the very pills they were tracking. During the raid, the task force caught a dealer carrying a plastic bag filled with green pills labeled Tafrodol, Aveo’s brand, complete with its company logo.

And Tamale isn’t alone. The same pills have been found in Nigerian and Ivoirian markets, where teenagers often mix them with alcoholic energy drinks to amplify the high, further increasing the danger.

Booming Black Market & Lax Regulations

Publicly available export data reveal that Aveo Pharmaceuticals, along with a sister company, Westfin International, has shipped millions of these tablets to West Africa. The largest market is Nigeria, home to 225 million people, where the National Bureau of Statistics estimates that around four million Nigerians abuse some form of opioid.

“This is devastating our youths, our families. It’s in every community in Nigeria,” said Brigadier General Mohammed Buba Marwa, Chairman of Nigeria’s Drug and Law Enforcement Agency (NDLEA).

Alarmingly, Aveo’s pills are even more dangerous than the previously popular opioid tramadol, which has been widely abused in West Africa for years. According to Dr. Lekhansh Shukla, assistant professor at India’s National Institute of Mental Health and Neuro Sciences, tapentadol is a powerful opioid that causes deep sedation. When mixed with carisoprodol, the risk of overdose increases drastically.

“It could be deep enough that people don’t breathe, and that leads to overdose,” Dr. Shukla explained. “And along with that, carisoprodol gives deep relaxation. It’s a very dangerous combination.”

Carisoprodol is banned in Europe and tightly regulated in the U.S., where it’s only approved for short-term use. Withdrawal symptoms can include anxiety, insomnia, and hallucinations. When combined with tapentadol, Dr. Shukla warns, the withdrawal is even more severe.

“This is not something that is licensed to be used in our country,” he emphasized.

Breaking Laws, Destroying Lives

In India, pharmaceutical companies are prohibited from manufacturing or exporting unlicensed drugs unless the importing country has approved them. However, Ghana’s National Drug Enforcement Agency confirmed that the combination of tapentadol and carisoprodol is unlicensed and illegal in the country. By shipping these drugs to Ghana, Aveo is directly violating Indian law.

When confronted by the BBC, neither Aveo Pharmaceuticals nor Vinod Sharma responded to the allegations.

India’s national drug regulator, the Central Drugs Standard Control Organization (CDSCO), stated that the government is committed to safeguarding global public health and is tightening regulations. It has pledged to investigate the matter and coordinate with West African authorities to crack down on illegal pharmaceutical exports.

However, Aveo is not the only company involved. Other Indian pharmaceutical firms are producing similar opioids, contributing to a crisis that is undermining the credibility of India’s $28 billion pharmaceutical industry, a sector known for producing life-saving generic drugs and vaccines.

“Nowadays, This Is Business”

The BBC’s undercover operative reflected on his encounter with Vinod Sharma, noting the cold indifference displayed by someone at the core of West Africa’s opioid epidemic.

“Nigerian journalists have been reporting on this opioid crisis for more than 20 years, but finally, I was face-to-face with one of the men who actually makes this product and ships it into our countries by the container load,” the operative said. “He knew the harm it was doing, but he didn’t seem to care… describing it simply as business.”

In Tamale, the local task force continues its grassroots battle against the opioid invasion. During a final raid with the BBC team, the group seized hundreds more packets of Tafrodol. That evening, in a public display, they set the drugs ablaze in a local park.

“We are burning it in an open glare for everybody to see,” said Zickay, a community leader, as the flames rose. “It sends a signal to the sellers and the suppliers: if they get you, they’ll burn your drugs.”

But while local communities do what they can to stem the tide, the real fight lies thousands of miles away, in the factories of Mumbai, where pharmaceutical companies like Aveo continue to profit from the suffering of millions. Until stricter global regulations and tougher enforcement are in place, the opioid crisis in West Africa is far from over.

RELATED: